The United Nations declared October 11th the International Day of the Girl Child. Everywhere I looked for this post’s inspiration, I saw story after story of the daily violence perpetrated against girls worldwide. I had to ask myself, why just a day? Aren’t girls – roughly half of the world’s population – deserving of much more consideration? I say that we declare 2017 the YEAR of the Girl and devote our efforts to address the following issues.

Female Genital Mutilation

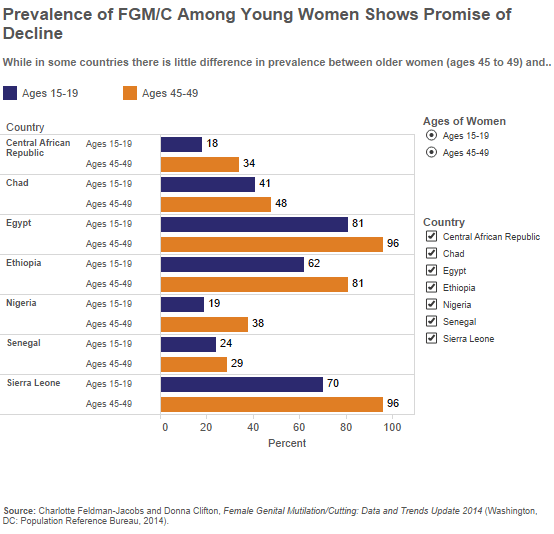

Female genital mutilation, or FGM, is a global concern. Some 200 million girls and women in 30 countries have undergone FGM, usually between infancy and 15 years of age. In many countries, FGM is a deeply entrenched cultural practice that has seen little decrease in the decades since foreign aid workers have been campaigning for is abolition. The risks might be high – infection, infertility, and complications of childbirth – but the perceived social benefits outweigh the physical costs. Bettina Shell-Duncan, an anthropology professor working as part of a five-year research project by the Population Council, has witnessed this conflict firsthand among the Rendille people of Northern Kenya:

One of the things that is important to understand about it is that people see the costs and benefits. It is certainly a cost, but the benefits are immediate. For a Rendille woman, are you going to be able to give legitimate birth? Or elsewhere, are you going to be a proper Muslim? Are you going to have your sexual desire attenuated and be a virgin until marriage? These are huge considerations, and so when you tip the balance and think about that, the benefits outweigh the costs.

Despite cultural ties, FGM is decreasing in some African countries as evidenced by rates from the prior generation. However, with prevalence as high as 81% (Egypt), 79% (Sierra Leone), and 62% (Ethiopia), there is still much work to be done.

For example, with prevalence at 60-70%, FGM in Iraqi Kurdistan is a “hidden” epidemic. Prevalence of this practice elsewhere in Iraq is 8%. Outlawed in 2011 by the Kurdistan Regional Government under the Family Violence Law, FGM has continued largely unabated due to poor implementation and push-back from religious leaders. You can read the Human Rights Watch harrowing report about FGM in Iraqi Kurdistan here.

Rape and Child Marriage

Last Friday, the BBC reported on a bill under consideration by the Turkish Parliament that would clear a man of statutory rape if he married his victim. This bill is evidence of increasing violence against Turkish women. Between 2003 and 2010, the murder rate of women increased by 1,400%. Of course, the bill isn’t couched in terms of legalizing rape, but as a loophole for those offenders who know not the errors of their ways:

The aim, says the government, is not to excuse rape but to rehabilitate those who may not have realised their sexual relations were unlawful – or to prevent girls who have sex under the age of 18 from feeling ostracised by their community.

If passed, the bill would release 3,000 men from prison as well as legitimize child rape and marriage. Per Girls Not Brides, Turkey has one of the highest child marriage rates in Europe with 15% of girls married before the age of 18. Globally 34% of women are married before the age of 18 and every day 39,000 girls join their ranks. According to a study recently published in the International Journal of Epidemiology, child marriage comes with health and social consequences. Along with unintended pregnancies, infant and maternal mortality, and HIV, girls who are married suffer from social isolation, power imbalance, and experience higher lifetime rates of physical and sexual intimate partner violence.

Coming-of-age “Cleansing” Rituals

Practiced in parts of Africa, girls as young as 12 are forced to have sex as part of a sexual cleansing ritual. The men, known as “hyenas,” are paid by parents to usher girls through the transition between girlhood and womanhood. Girls are coerced into this practice through familial and societal pressure. It is believed that great tragedy will befall the family and community should she not comply. The use of a condom is prohibited.

A BBC radio broadcast found that communities believe the spread of HIV to be a minimal risk since they can pick men they know are not infected. One Malawian hyena, Eric Aniva, has been charged with exposing hundreds of girls and women to HIV. Aniva knew of his HIV status but did not disclose to his customers.

Forty percent of the global burden of HIV infections are in Southern Africa. Thirty percent of new infections in this area are in girls and women aged 15-24. Young women contract HIV at rates four times greater than male peers and 5-7 years earlier, linked to sexual debut or sexual cleansing rituals.

Let’s face it: Girls around the globe are being short-changed. Though progress has been made, there is still much work to be done. The Sustainable Development Goals have promised to “end all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere” by 2030. Others attest that it will take at least another century for women to reach wage equity in the United States. However it happens, rest assured it will take more than a day.