Dr. Naser AlMhawish speaks with admiration for his fellow health care workers in Syria. A surgeon turned surveillance coordinator for the Assistance Coordination Unit (ACU), he describes how a colleague smuggled himself into a village stuck between conflict groups and gathered potential polio samples. Before returning the samples to Turkey, the colleague was arrested and questioned.

“They couldn’t understand that someone would risk his life [to carry samples],” said AlMhawish, noting the samples were eventually used to identify an outbreak. Other members of the team have been attacked and even killed while working to end polio. In some areas, AlMhawish said the association with an organization like ACU made otherwise routine health work “like a suicide mission”.

Prior to joining ACU, AlMhawish practiced surgery in his home town of Raqqah, Syria, where he survived bombings and faced ethical dilemmas. “You are dealing with patients regardless of their background,” he said, remembering the messages he posted at a hospital announcing “No Guns Allowed”. He had to leave Syria when it became impossible to avoid coercion to work for conflict actors.

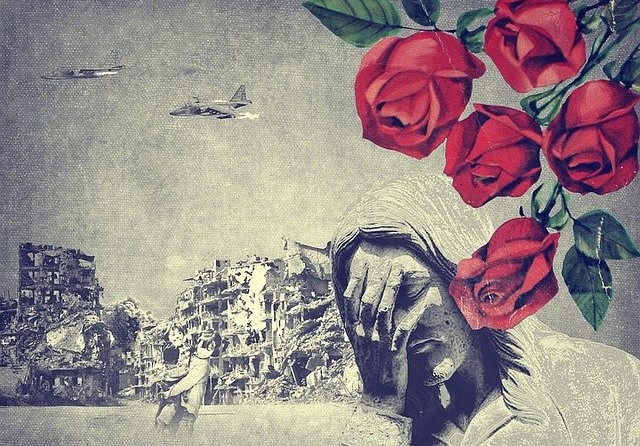

Dr. Fadi Hakim, advocacy manager at the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS), worked in similar circumstances. Before his displacement from Syria, Hakim practiced in Eastern Aleppo where he was the only dentist for miles. “I was myself subjected to attacks on facilities while I was inside,” he said. “It is really terrifying when you hear the jet…when you start to hear the barrel bomb falling down over your head, and you don’t know whether it’s going to fall down on you or next to you”.

He cited the experiences of friends and coworkers surviving multiple attacks and the impact to their mental health and family life. “Imagine the family’s reaction every time they hear about a hit,” he said, “the children always saying bye to dad, not sure if he is coming back or not.”

Both Hakim and AlMhawish work with Dr. Rohini Haar, an APHA International Health (IH) section member, to demonstrate the impact of attacks on population health. An emergency physician in Berkeley, California, Haar began researching attacks on health with human rights lawyer and IH section member Leonard Rubenstein in Myanmar.

Rubenstein is a past president and executive director of Physicians for Human Rights and current chair of the Safeguarding Health in Conflict Coalition (SHCC) which raises awareness about, strengthens documentation of, and empowers local groups to demand accountability regarding attacks on health.

These efforts mingle with the work of IH governing councilor Dr. Samer Jabbour, a cardiologist and professor at the American University of Beirut. Jabbour chairs the Lancet-AUB Commission on Syria which introduced the concept of weaponisation of health.

Several additional collaborations and surveillance initiatives emerged during the past decade, including the WHO’s Surveillance System of Attacks on Healthcare (SSA) and the ICRC’s Health in Danger (HCiD) project. In 2016, United Nations Security Council Resolution 2286 was adopted to extend provisions of international law for healthcare personnel and facilities in conflict situations. In 2019, an APHA policy statement outlined a research agenda and called for protection of health workers and health facilities in war.

Despite other encouraging developments, such as the launch of criminal trials and a recent conviction on crimes against humanity in Syria, attacks on health continue with impunity. “What’s happening is a scandal,” said Hakim, “This is a terror tactic. We are just being hit and nobody seems to care except for sending a statement, condemning, etc.”

While documentation and reporting remain an important part of the accountability and justice process, researchers like Jabbour and Haar express the need to demonstrate impacts on population health. Jabbour said the research should also measure “the efficacy of interventions” like the 2286 Resolution which turned five years old in March.

Various efforts are already underway. In addition to forthcoming research from the AUB-Lancet Commission, Hakim and AlMhawish are working with Haar at the University of California, Berkeley. The Researching the Impact of Healthcare (RIAH) consortium includes Rubenstein and Haar as co-investigator and researcher, respectively. SHCC also recently released a report, “Ineffective Past, Uncertain Future”, that concluded an “absence of follow-through on these commitments” and called for appointment of a special representative or monitor on the UN Resolution’s implementation.

SAMS will continue to focus on violations of international humanitarian law (IHL), said Hakim, including attacks on health care workers and facilities. “Recently we are getting more focused on accountability issues and… building of cases with the hope to be able to someday go to courts and be able to have accountability,” he said.

Other challenges also remain. In addition to the constant threat of violence, for example, AlMhawish wonders about the next funding cycle. “In the field we have more than 200 working,” he said. “So 200 families, and with the economic situation, yes—funding is critical for us.”

With COVID-19 exacting even more stress on the tenuous health workforce, humanitarian access, and funding sources, the situation looks bleak. “We said to ourselves we will not stay silent about what is happening,” said Hakim. “Sometimes people say everybody is tired from hearing about Syria. Ok, let it be so. We want everyone to be tired about what’s happening in Syria. We don’t want to stay silent about what is happening. Because unfortunately right now, this is the only thing that we have.”

As population health impacts of attacks on conflict are more effectively measured and additional voices appeal for justice from governments and policy makers, will perpetrators finally be brought to heel?

Reblogged this on anlan cheney.